#116

the art of apologizing

In her paper Owning up and lowering down: The power of apology, Adrienne M Martin writes:

Apologies are strange. They are, in a certain sense, very small. An apology is just a gesture—a set of words, a physical posture, perhaps a gift. But an apology can also be very powerful—this power is implicit in the facts that it can be difficult to offer an apology and that, when we are wronged, we may want an apology very much. More, even if we have been severely wronged, we are sometimes willing to forgive or pardon the wrongdoer if we receive a sincere apology.

Last week, I asked for an apology.

One I knew I deserved, one that was due, for a violation of my privacy that went on for over a year. I approached the situation with curiosity and generosity, I was willing, open, and vulnerable. Of course I felt anger —deep anger— but it was anger I was willing to explore, to understand. This is the state required for a true apology. The ego has to fuck off, at least long enough to release its grip on the mind and soul, affording one a length of freedom to speak from the heart.

Earlier this month, I wrote about grudges, how I’ve never been able to hold one. As I type this, I realize I tempted fate by doing so. God had to ask: are you sure about that, Sara?

Oops. Thirty e-mails later, I am not so sure.

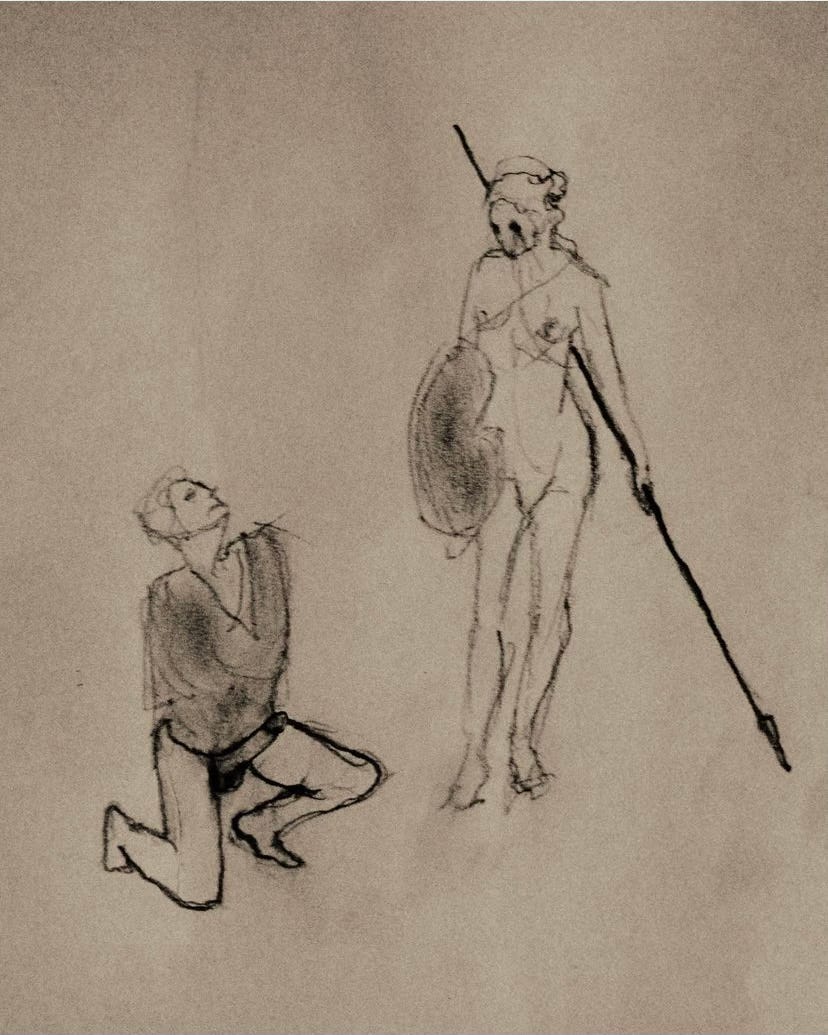

Apologies are a dance, un pas de deux. Adagio; slow, careful, intentional. He always told me he can’t dance, and I saw it then, again and for the first time somehow: the clumsy, self-centered, impulsive and impatient child that he is. The tempo of someone trying to run away from his shame.

The dance is preposterous, the conclusion impossible, a mutilated end pose; no one catches me. I do not get a solo.

There is a paradox to apologies— can humility really co-exist with the intention driving the apology itself? Does the aim always pervert the act? Perhaps. Still I am not that cynical, I know I have felt true regret, given sincere apologies, and it is precisely because I have that I know others can too, that I keep my heart open to the possibility of absolution.

I believe the moral function of an apology is to restore a sense of balance to a situation that lacks it. Expressing true remorse or witnessing it reminds us of our humanity. A sincere apology makes itself obvious—it is Naked—we know it when we see it. In the same way, an insincere or calculated apology sets something off in our gut, fails to provide solace, and instead invites more questions, even dressed in all the right words.

Confronted with the formulaic or robotic, it is impossible to access tenderness.

I type:

I cannot accept this apology, which makes a mockery of both of us. Your forced formality barely masks the contempt you still feel for me, and the rage you feel at being found out.

and he responds: injecting emotions into this is not useful.

I sit there and wonder what he thinks emotions are for.

And for the first time in my life, I do not forgive.

Realism Confidence is a reader-supported publication. If you’d like to support my writing (or help me go to the dentist), please consider becoming a paid subscriber, buying a subscription for someone else, or, if you like what you’re reading, you can send me a tip via Paypal. Feel free to follow me here or here.